Home > A. E. van Vogt > THE 83 VAN VOGT STORIES ON THIS SITE > "The Shadow Men" (1950) — an outstanding golden-age novella by A. E. van (…)

"The Shadow Men" (1950) — an outstanding golden-age novella by A. E. van Vogt never before republished

"The Shadow Men" (1950) — an outstanding golden-age novella by A. E. van Vogt never before republished

Tuesday 3 September 2013, by

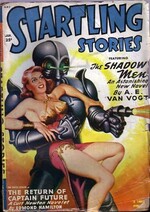

This striking tale from the golden age of science-fiction was never republished in either magazine or book form after its initial appearance in the January 1950 issue of Startling Stories, where it was highlighted on the quite spectacular cover [1] by Earle Bergey

With its 36,400 words – the equivalent of some 110 pocket-book pages – it is technically a (long) novella, according to the criteria developed by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America association: short story - under 7500 words; novelette - 7,500 to 17,499 words; novella - 17,500 to 40,000 words; novel: 40,000+ words; although it was announced as a novel in the magazine.

Otherwise, with its complex structure – 18 named chapters –, its ambitious themes – crime and punishment, time-travel paradoxes, the sociological divisions of the America of the future – and its well-developed psychological and period atmosphere, this novella certainly does conform to what one can and should expect of a fully-developed novel.

The text of The Shadow Men was integrated into the 1953 "fix-up" novel The Universe Maker with very extensive changes and a great deal of additional material. For this reason the original story was no doubt never republished, much in the same spirit that the crime-thriller writer Raymond Chandler had adopted after the publication in 1939 of his celebrated opus The Big Sleep, that had been composed almost entirely of previously-published magazine stories that Chandler refused to have published in book form during his lifetime.

An overview of The Shadow Men can be consulted here.

An e-book version is available for downloading below.

CHAPTER I - Therapy - To Be Murdered

(Chap. IX)

LIEUTENANT MORTON CARGILL staggered as he came out of the cocktail bar. He stopped and was turning, instinctively seeking support, when a girl emerged from the same bar. She half fell against him.

They clung to each other, maintaining a precarious balance. She seemed to recover first. She mumbled, " ’Member, you promised to drive me home."

"Huh?" said Cargill. He was about to add, "Why, I’ve never seen you before."

He didn’t say it because it suddenly struck him that he had never before in his life been so drunk either. And there was a vagueness about the last hour that lent a sort of a plausibility to her words.

He certainly had intended to find himself a girl before the evening was over.

Besides, what did its matter anyway? This was 1943. He was a man who had three days left of his embarkation leave and he couldn’t stop to argue about the extent of his acquaintance.

"Where’s your car?"

She led the way, weaving, to a Chevrolet coupe. He had to help her unlock the door and she collapsed onto the seat beside the steering wheel, her head hanging limply. Cargill climbed behind the wheel and almost slid to the floor.

For a moment that pulled him out of his own blur.

He thought, startled, "I’m not fit to drive a car either. I’d better get a taxi."

The impulse faded. He was a man who had three days left of his leave. As of right now the pickup was a fact, whatever its history, and he was just tight enough not to have any qualms. He stepped on the starter.

* * * * *

Cargill made the first effort to get out of the car after the crash. The door wouldn’t open. His attempt at movement made him aware of how squeezed in he was. Dazed, he realized that he had escaped death and injury by a miracle.

He tried to reach across the girl toward the door on her side — and got his second big shock.

The whole front of the car was staved in.

Even in the half darkness Cargill realized that the blow had been mortal. In a spasm of comprehension of what this could mean he made a new effort to open his own door. This time it worked. He staggered out and off into the darkness. No one tried to stop him, no one saw him.

In the morning, pale and sober, he read the newspaper report of the accident:

GIRL’S BODY FOUND IN WRECK

Her car smashed beyond repair when it sideswiped a tree, Mrs. Marie Chanette last night bled to death from injuries sustained in the accident. The body was not discovered until early this morning and it is believed the victim might have been saved had she been found sooner and treated.

Mrs. Chanette, who was separated from her husband recently, is survived by a three-year-old baby girl and a brother, said to be living in New York. Funeral arrangements await word from relatives.

There was no mention of a possible escort. A later edition mentioned that she had been seen talking to a soldier, and that paragraph was enlarged upon in the evening paper. By the second morning there was talk of murder in the news columns, and an amazingly accurate description of the soldier was given. The wretched Cargill took alarm, and returned gloomily to his camp.

He was relieved a week later when his division was sent overseas. It put three years between him and the impulse that had made him scamper off into the darkness, leaving behind him a dying woman. Battle experience hardened him against the reality of death for other people and slowly the awful sense of guilt faded. Completely recovered, he returned to Los Angeles early in 1946. He had been home several months when a note arrived for him in the morning mail:

Dear Captain Cargill:

I saw you on the street the other day and I noticed your name was still listed in the phone book. I wonder if you would be so kind as to meet me at the Hotel Gifford tonight (Wednesday) at about 8:30.

Yours in curiosity,

Marie Chanette.

Cargill read the note, puzzled, and for just a moment the name meant nothing to him. Then he remembered. And then —

"B—but," he thought, stunned, "she never knew my name."

It required minutes to shake off the chilling sensation that stole along his spine. At first he decided against turning up but as evening arrived he knew he couldn’t remain away.

"Yours in curiosity!" What did she mean?

It was 8:15 when he entered the foyer of the magnificent Gifford and took up a position beside a pillar from which he could watch the main entrance.

He waited.

AT 9:30, he retreated, blushing from his fifth attempt to identify Marie Chanette.

He hadn’t noticed the man behind the column who was talking to the girl. The girl was smiling sweetly now, the secret smile of a female who has won the double victory of defending her virtue and simultaneously proving that she is still attractive to other men.

Her gaze turned fleetingly, knowingly and touched Cargill’s eyes, then her attention swung back in a proprietary fashion to the young man. She smiled once more, too sweetly. Then she took her escort’s arm and they moved off through a door above which floated a lighted sign that said alluringly, DREAM ROOM.

The high color faded from Cargill’s cheeks as he took up his position once more. But his determination was beginning to wane. Five women had now repulsed him and that was too strenuous for any one evening.

A big man moved up beside him. He said softly, "Captain, how about peddling your wares in some other hotel? Your repeated failure is beginning to embarrass the guests. In other words, move on, bud, move on. And fast."

House dick — Cargill stared at the other’s smooth face with a pale intensity. He was about to slink off when a young woman’s voice said clearly. "Have I kept you waiting long, Captain?"

Cargill swung around in glassy-eyed relief. Then he stopped. His brain roared. He mumbled, "You’re Marie Chanette."

She was changed but there was no doubt. It was she. Out of the corner of one eye he saw the house detective move off, baffled. An impulse came to call the man back.

Even as the thought came he forgot the fellow. For his fascinated brain, there was only the girl.

"It really is you," he said. "Marie Chanette!"

Her name came hard from his tongue as if the words were pebbles that interfered with his speech. He began to realize how changed she was, how different.

The girl he had picked up three years before had been well dressed but not like this. Now she wore a "hot pink" sari with a fur coat of indeterminable animal lightly held over her shoulders, the most glittering coat Cargill had seen since his return to America.

Her clothes ceased to matter. "But you’re dead," he wanted to say. "I read the account of your burial."

He didn’t say that. Instead he listened as the girl murmured, "Let’s go into the bar. We can talk about — old times — over a drink."

Cargill poured down the first drink without pausing. Then he looked blurrily at the girl. And saw that she was watching him with a faint indulgent smile.

"I wondered," she said, "what it would be like to come back and have a drink with a murderer. It’s really not very funny, is it?"

Cargill began to gather his defenses. There was something here he didn’t understand, a purpose deeper than appeared on the surface. He had seen suppressed hostility too often not to recognize it instantly. This woman was out to hurt him and he had better watch himself.

"I don’t know what you mean," he said sharply and his voice had a faint snarl in it. "I’m not sure that I even know you."

The woman did not answer immediately. She was doing something to her purse. It opened abruptly. She reached in and took out two large photographs. She tossed them across the table without a word.

IT gave Cargill several seconds to focus his unsteady gaze on the prints. His eyes and his mind coordinated finally, and with a gasp he snatched them up.

Each one showed a man in an officer’s uniform in the act of climbing out of a badly wrecked car. The realism of the scenes almost stopped Cargill’s breath. One of the prints showed the girl pinned by the door on her side. Her face was twisted and blood was streaming down over her eyes.

The second print was a full face of the officer, taken on an upward slant from an almost impossible position behind the girl.

Both prints showed the officer’s face and both showed him squeezing out of the partly open door on the driver’s side.

In each ease it was his own countenance.

Cargill let the prints drop from limp fingers and stared at the girl with eyes that narrowed with calculation. "What do you want?" he asked harshly. Then more violently, "Where did you get those pictures?"

The last question galvanized him into action. He snatched the prints as if defending them from her, as if they were the only evidence against him. With tensed fingers he began to rip them into tiny pieces.

"You may keep those copies," said the girl calmly.

Copies! Cargill shifted his feet and he must have looked up. For a waiter darted forward and he heard himself ordering drinks. And then the whisky was back and he was pouring it down into his burning throat. He thought more sanely that, if she were alive, no charge could be brought against him after all this time.

He saw that she was fumbling in her purse. She drew forth a glittering cigarette and, putting it in her mouth, took a deep puff, then exhaled a thin cloud of smoke. Without seeming to notice his gaze fastened on the "cigarette" she delved once again into her purse, this time came out with a card the size of a streetcar pass, tossed it across the table at him.

"You will be wondering," she said, "what this is all about. There, that explains to some extent. Suppose you look at it."

CARGILL scarcely heard.

"That cigarette," he said. "You didn’t light it."

"Cigarette?" She looked puzzled, then she glanced in the direction of his glare. Understanding dawned. She reached once more into her purse, and came out with a second cigarette similar to the one she was smoking. She held it out to him.

"It works automatically," she said, "every time you draw on it. Very simple but I’d forgotten they won’t be available for a hundred years yet. Very soothing they are."

He needed it. The cigarette seemed to be made from some kind of plastic but the flavor was pure mild tobacco. Cargill drew on it deeply three times. Then, his nerves steadier, he forgot the uniqueness of such a cigarette and picked up the document she had thrown on the table. A luminous print stared up at him

THE INTER-TIME SOCIETY FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL ADJUSTMENTS

recommend

READJUSTMENT THERAPEUTICS

for

Captain Morton Cargill

June 5, 1946

CRIME: MURDER

THERAPY: TO BE MURDERED

The sinking sensation that came to Cargill had in it a consciousness of darkness gathering over his mind. He was aware of a boogie-woogie record starting to play nearby. He shook himself blurrily. Through a thick mist he gazed at the girl. "This is silly," he muttered. "You’re kidding me."

She shook her head. "It isn’t me. Once I went to them it was out of my control. And as for you the moment you picked up that card you were —"

Her voice retreated into a remote distance as the shadows swept in over him. There was night.

CHAPTER II - Escape in Time

THE blackness ended but his vision remained blurred.

(Chap. XIV)

The obstruction cleared away after he had blinked hard for several seconds. Automatically he looked around him.

At first, he did not clearly realize that he was no longer in the DREAM ROOM. There was a tremendous difference but for a moment his mind made a desperate effort to justify a similarity. He tried to think of the cocktail bar as having been stripped of its furniture.

The illusion collapsed. He saw that he was sitting in a chair at one end of a tastefully furnished living room. To his left was an open door through which he could see the edge of a bed. The wall directly across from him was a mirror.

Once more he had to make an adjustment. For as he looked into the "mirror" he saw that there was a girl sitting in what would have been the mirror image of his own chair. It was the girl who resembled Marie Chanette.

Cargill started to his feet. In two minutes, in a frenzy of uneasy amazement, he explored the apartment. The door he had seen when his vision first cleared led to a bedroom with attached bathroom. The bathroom had a connecting door but it was locked. The living room wall was not a mirror at all but a window.

Beyond it was a virtual duplicate of the apartment he was in. There were the same living room and the same door leading to another room — Cargill could not see if it was a bedroom but he presumed that it was. On one wall of the living room was a clock that said: "May 6, 6:22 P.M." It had obviously stopped working a month ago.

He had been moving with a feverish excitement. Now he retreated warily to a chair and sat there, glaring at the girl. He remembered what she had said in the cocktail bar — remembered the card and its deadly threat.

He was still thinking about it when the girl climbed to her feet and came over to the glass barrier. She said something or rather her mouth moved as if in speech. Not so much as a whisper of sound came through. Cargill was galvanized. He plunged up from his chair, and yelled, "Where are we?"

The girl shook her head. Baffled, Cargill explored the wall for a possible means of communication. Then he looked around the room for a telephone. There was none. Not, he reflected presently, in a brief fury of self-anger, that a phone would have done him any good. There was such a thing as having a phone number to call. Another thought struck him. Frantically he searched for pencil and paper in the inside breast pocket of his coat. Sighing with relief, he produced the materials. His fingers trembled as he wrote Where are we?

He held the paper against the glass. The girl nodded her understanding and went back to get her purse. Cargill could see her writing in a small notebook, then she was back at the glass barrier. She held up the paper. Cargill read, I think this is Shadow City.

That was meaningless. Where’s that? Cargill wrote.

The girl shrugged and answered, Somewhere in the future from both your time and mine.

That calmed him. He had his first conviction that he was dealing with queer people. His eyes narrowed with calculation. Cautiously he considered the danger to himself of a cult that put forward such nonsense. The girl was forgotten, and he went back slowly and settled down in the chair.

"They won’t dare harm me," he told himself.

Just how it had been worked he couldn’t decide. But apparently the family of Marie Chanette had somehow discovered the identity of the man who had been with the girl when she was killed and in the distorted fashion of kinfolk, blamed him completely for the accident.

He had no sense of guilt, Cargill told himself. And he certainly had no intention of accepting any nonsense from a bunch of neurotic relatives.

Anger welled up in him, directed now and no longer stimulated by fear and confusion. A dozen plans for counteraction sprang full-grown into his mind. He’d break the glass, smash the door that led from the bathroom, break every stick of furniture in the room.

These people were going to regret even this tiny action they had taken against him. For the third time, with deliberation now, he climbed to his feet. And he was hefting a chair for his first attack when a man’s voice spoke at him from the air directly in front of him.

"Morton Cargill, it is my duty to explain to you why you must be killed."

Cargill remained where he was, rigid.

HE unfroze swiftly. As his mind started to work again he looked wildly around him, seeking the hidden speaker from which the voice had come. He assumed that it had been mechanical. He rejected the momentary illusion that the voice had come from mid-air.

His gaze raked the ceiling, the floor, the walls, in vain. He was about to explore more thoroughly with his fingers, with his eyes close up, when the voice spoke again, this time almost in his ear.

"It is necessary," it said, "to talk to you in advance, because of the effect on your nervous system."

The meaning scarcely penetrated. He was fighting a sense of panic. The voice had come from a point only inches away from his ear and yet there was nothing. No matter which way he turned the room was empty. And there was no sign of any mechanical device. Definitely there was nothing that could have produced the illusion of somebody speaking directly into his ear.

For a third time, the voice spoke, this time from behind him. "You see, Captain Cargill, the important thing in such a therapy as this is that there be a readjustment on the electro-colloidal level of the body.

"Such changes cannot be artificially induced. Hypnosis is not adequate because no matter how deep the trance, there is a part of the mind that is aware of the illusion.

"You will readily see what I mean when I say that even in cases of the most profound amnesia you can presently tell the subject that he will remember everything that has happened. The fact that that memory is here, capable of recall under proper stimulus, explains the prolonged therapies sometimes necessary even with hypnosis."

This time there was no doubt. The speech was long, and Cargill had time to turn around, time to assure himself that the voice was coming from a point in the air about a foot or so above his head. The discovery shocked some basic point of stability in him.

He had let go of the chair with which he had intended to smash the furniture. Now he snatched it up again, He stood with it clenched in his hands, eyes narrowed, body as stiff as the wood of the chair itself, and listened as once more that disembodied voice spoke.

"Only a fact," it said inexorably, "can affect quick and violent changes. It is not enough to imagine that a machine is bearing down upon you at top speed, even if the imagining is accomplished in a state of deep hypnosis.

"Only when the machine actually rushes at you and the danger is there in concrete fashion before your eyes — only then does doubt end. Only then does every part of the mind and body accept the reality."

Cargill was beginning to lose some of his own doubts. He had his first sharp feeling that this was real. Here were not just a few angry relatives. He let go of the chair and began to relax.

Here was danger, definite, personal, immediate. And that was something that he could face. For more than three years he had been conditioned to a series of reactions when he was threatened — a remorseless alertness and an almost paradoxical combination of keyed-up relaxation.

He said now, "What is all this? Where am I?"

That was becoming tremendously important. He needed information now to stabilize himself. This situation was new and different from anything that he had ever experienced before. And what was particularly vital was that he had taken the first step necessary to combating it. He accepted its reality.

Someone was doing something against him. Whoever it was had enough money to set up these two rooms in this curious fashion. It looked very expensive. It was convincing. From the air the voice, ignoring his questions, went on.

"It would not be enough to tell the descendants of Marie Chanette that you had been killed. The girl has to see the death scene. She has to look down at you after you have been killed. She has to be able to touch your cold flesh and realize the finality of what has happened. Only thus can we assure adjustment on the electro-colloidal level."

The Voice finished quietly. "But now I would suggest that you rest awhile. My words need time to sink in. You will hear from me again in the evening — for the last time."

Cargill did not accept the finality of the words. For several minutes he asked questions, talking directly at the point from which the voice had come. There was no reply. In the end, grim and determined, he gave up that approach, and returned to an earlier more violent one.

For ten minutes he smashed a chair against the glass barrier. It was a case of smashing. The wooden chair creaked and vibrated from each blow and shattered section by section. The glass was not even scratched.

Reluctantly, Cargill accepted its impregnability. He headed for the bathroom, and tested the door that led from it. He gave one tug at the knob and his heart sank. The door was made of a hard metal. For an hour he worked on it without once affecting it in any visible fashion.

He headed for the bedroom finally and lay down, intending to rest briefly. He must have fallen asleep instantly.

SOMEBODY was shaking him violently. Cargill came out of the stupor of sleep to the sound of a woman’s voice saying urgently in his ear, "Hurry! There’s no time to waste. We must leave at once."

He was a man who expected to be murdered and that was his first memory. He jerked so spasmodically it seemed as if his body would tear.

And then he was sitting up.

He was still in the bedroom of the apartment with the glass wall. And the girl who was bending over him was a complete stranger.

As he glared at her she stepped back from him and bent over a small machine. Her profile was to him, intent now and almost girlish in the anxiety that was there. Something must have gone wrong, for she began to curse in a most ungirlish fashion in a low tone. Abruptly, in a kind of desperation, she looked at him.

"For — sake" — Cargill didn’t get the word —" don’t just sit there. Come over here and pull on this jigger. We’ve got to get out of here."

He was a man who was trying to grasp many things at once. His gaze flicked apprehensively toward the open door.

"Ssssssh!" he whispered instinctively.

The girl’s eyes followed his gaze. "Don’t worry about them — yet. But quick now l"

Cargill came heavily. His mind held him down. Her presence baffled him.

He knelt beside her — and grew aware of the faint perfume that emanated from her body. It gave him a heady sensation. For a moment, the tiny pin she was tugging at wavered in his vision. And then once more the girl spoke.

"Grab it," she said, "and pull hard."

Cargill sat there. The expression on his face must have penetrated to her at last for she paused and looked at him hard.

"Oh, mud," she said — it sounded like "mud" — "tell mother all about it. What’s eating you?"

He couldn’t help it. His mind was twisting, turning, writhing with doubts and fears.

"Who are you?" he mumbled.

The girl sagged back. "I get it," she said. "Everything’s too fast. You haven’t had time to think. You poor grud you." It sounded like grud. She was shrugging. "Fine, we’ll stay here until one of the Shadows comes."

"The what?"

The girl moaned. "Oh, Mud, won’t I ever learn to keep my mouth shut. I’ve started him off again."

Her tone cut him at last. A flush touched his cheeks.

"Blast you!" he said, "What’s all this about? What are you doing here? What—?"

The girl held up one hand as if to defend herself from attack. "All right, all right," she said. "I give up. Let’s sit down and have a cozy chat, shall we? My name is Ann Reece, I was born twenty-four years ago in a hospital. I spent my first year more or less lying on my back. Then —"

The anger she aroused in him acted like an astringent. It tightened his thoughts and pulled back a dozen wandering impulses into a sort of unity. His very intentness must have impressed her. She parted her lips as if to say something light. Then looked at him — and closed them again.

Then she said, "Maybe we’re going to get somewhere, after all. All right, my friend, a minute ago I wouldn’t have told you anything. You’ve been pulled out of the twentieth century to the — well, the present. And that’s all I’m going to tell you about that. I belong to a group who are opposed to the Shadows. And I was sent here after you —"

She stopped. Her brows knitted. "Never mind! Now, please, don’t ask me how we knew you were here. Don’t ask any more questions. This machine brought me into this room in the heart of Shadow City and it will take the two of us out if you will unjam that pin.

"If you don’t want to go with me, loosen the pin anyway, so that I can get to" — Cargill missed the word completely — "out of here. You can stay and be murdered for all of me. Now, please, the pin!"

Murdered! That did it. It wasn’t that he had forgotten. It was the insensate wriggling of his brain that pushed that danger into the background. He leaned forward, his fingers forming to take hold.

"Do I pull or push?" he breathed.

"Pull."

Cargill snatched at it. The first touch startled him. It was as if he had grasped a film of oil. His skin slid over the immense smoothness of it as if there was nothing there. He grabbed again, sweating abruptly with the realization of the problem.

"Jerk!" said the girl harshly.

He jerked. And felt the slight tug as it yielded a fraction of an inch.

"Got it!" It was his own voice, hoarse triumph.

The girl reached past him. "Quick, grab that smooth bar." Even as she spoke her hand guided his. He snatched for a hold. Her hand clutched the same bar just above where he was clinging.

He remembered then a dull glow from the bulbous section near his face. His body tingled.

And then he was lying on a hard smooth floor in a large room.

CHAPTER III - Planiac Captive

CARGILL did not look at the girl immediately. He climbed gingerly to his feet and put his hand to his head. It was an instinctive gesture, part of his utter absorption with himself. He found no pain, no dizziness, no sense of unbalance.

Why he had expected such reaction he didn’t know. The complete absence of unpleasant sensation made him feel better. He began to brace up to the situation. With brightening eyes, he glanced around the room. It was bigger and higher than his first impression had indicated. It was made of marble and seemed to be an anteroom. Except for minor seating arrangements for temporary visitors it had virtually no fur-niture.

There was a high arched doorway at either long end of the room but in each case the doors merely opened onto a wide hallway that ran at right angles to them. A single large window to Cargill’s left faced onto shrubbery, so he could not see what was beyond.

He was starting avidly for the window when he grew aware that the girl was watching him with an ironic smile.

Cargill stopped short and looked at her, "Why shouldn’t I be curious?" he asked defensively.

"Go right ahead," she said. She giggled. "But you look funny."

He stared at her angrily. She was a much smaller girl than he had thought and somewhat older. He remembered her language and decided — either older than twenty-five or younger. And unmarried. Young married women with children watched their tongues.

And besides, they didn’t go out risking their lives by joining exotic groups of adventurous rebels.

The shrewdness of the analysis pleased Cargill. It opened his taut mind a little wider. For the first time since leaving the cell, he thought, "Why, I’m way up in the future! And this time I’m free."

He had a sudden desperate desire to see everything before he was returned to the twentieth century. A will came, to know, to experience. He had a thrill of imminent pleasure. Once more he whirled toward the window.

Then once more stopped.

There was a memory in him of what the girl had said — "look funny."

He glared down at his body, naked except for a pair of something similar to gym shorts. It was not exactly indecent but Cargill felt irritated, as if he had been caught in an embarrassing position. His legs were hard and strong but they looked thinner than they actually were. He had never been at his best in a bathing suit.

He said in genuine annoyance, "You could have had some clothes waiting for me here. It’s getting chilly."

It was. Through the window he could see that it was also becoming darker. If he was still in California then the late afternoon sea breezes were probably blowing outside. Even in midsummer that meant coolness.

The girl said casually, "Oh, one of the men will bring you something. You’re to leave here as soon as it becomes dark."

"Oh!" said Cargill.

He shook his head as if he would drive out the blur that was confusing him. All these minutes he had been standing here, adjusting to the simpler aspects of his new environment. They were important, it was true, but they were the tiniest segment of all that was happening to him.

The restlessness of his brain, which had already brought so many spasms of memory and forgetfulness, derived from several major facts. He was in this far future world because an inter-time psychological society was using him to cure one of their patients.

The morality of that was a little too deep for Cargill but just thinking about it brought a surge of fury. Who did they think they were, murdering him to soothe somebody else’s upset nerves.

He fought down the anger, because that danger was temporarily behind him. Ahead was the mystery of the group that had rescued him and that, tonight, intended to take him — elsewhere.

Cargill parted his lips to ask the question that quivered in his mind when the girl said, "I’ll leave you here to look around. I’ve got to go and talk to somebody. Do not follow me, please."

She was at the door to the left of the window before Cargill could find his voice.

"Just a minute," he said. "I want to ask some questions."

"I don’t doubt it," said Ann Reece, with a low laugh. "You may ask him later." She turned, and was gone before he could speak again.

BEING alone soothed him. It was so marked a feeling that he realized how great had been the pressure upon him of the presence of other people while he was trying to adjust. Everybody else had plans about and for him. He had none for himself — except the window.

Peering out the window Cargill had the initial impression that he was looking onto a well-kept park. The impression changed. For through the latticework of the shrubbery he could see a street.

It was such a street as men dream about in their moments of magical imagination. It wound through tall trees, among palms and fruit trees. It had shop windows fronting oddly shaped buildings that nestled among the greenery.

Hidden lights spread a mellow brightness into the curves and corners of that ungeometrical artists’ street. The afternoon had become quite dark and every window glowed as from some inner warmth. He had a tantalizing vision of interiors that were different from anything he had ever seen.

All this was but a glimpse as viewed through the latticework of a rose arbor.

Cargill drew back, trembling. He had had his first look at Los Angeles of hundreds of years in the future. It was an exhilarating experience.

He took another long look but what he could see was too fragmentary to satisfy his expanding need. He retreated from that fascinating view, and peered through the door beyond which the girl had disappeared. It was a hallway and a drab light was shining along it, a reflection from another doorway some score of feet to the right.

He hesitated. Ann Reece had forbidden him to follow her but she had made no threats. He was still standing there, undecided, when he grew aware that a man and a woman were talking in the lighted room.

Cargill strained his ears. But he could hear nothing of what was said. It was the tone of the man’s voice that interested him. He seemed to be giving instructions and the girl was protesting.

Cargill recognized Ann Reece’s voice but how subdued she was! Her reaction dictated his own. This was not the time to barge in on her — better to sit down and wait.

He was halfway across the room, heading toward a chair, when his foot struck something that clanged metallically. It took a moment in the almost darkness to recognize the machine that had brought him and the girl out of the glass-walled room.

Gazing at it, conscious of the wonder of it, Cargill had a wild thought — if he could take this machine and sneak off into the descending night, then he’d be free not only of his original captors but of the new group with their schemes.

That last was important, now that he had heard the sharply unpleasant voice of the man in the next room.

Like a burglar in the night Cargill knelt beside the instrument. It was two-headed, like a barbell used by weightlifters. In the gloom, his quick eyes searched for the "pin" that had caused the earlier trouble. It was not visible.

Carefully, using only the tips of his fingers, he pushed the bar, rolling it slowly. It was warm to his touch but showed no other animation. Cargill withdrew his fingers. This was not really the time to test its potency.

Uncertain, he climbed to his feet — and grew aware that footsteps were coming along the hallway. He turned to face the doorway. The footsteps entered the room; there was a rustling sound and the place blazed with light.

A Shadow shape stood in the doorway.

HE was walking. It was hard to understand how it had happened, but he could feel the pressure of the dirt under his shoes and the play of muscles in his legs as they moved back and forth.

For a long time, in the reflection of the flashlight in the hands of the girl, he watched the rise and fall of her heels. Every little while she kicked up loose soil and it was that which suddenly shocked the blur out of Cargill’s mind.

The shadow figure, he thought. His legs continued their automatic movement but his brain flashed comprehension of his environment.

It was pitch dark. There was no sign anywhere of a city. He seemed to be walking along an unpaved rural road. Cargill looked up. But the sky must have been cloud-covered for he saw no stars and no moon.

Cargill groaned inwardly. What could have happened? One instant he was in a large marble anteroom inside a city, then the shadow shape had come in and seemed to examine him — one long look only. And then this — this dark road behind a silent companion.

"Ann!" said Cargill softly. "Ann Reece."

She did not turn or pause. "So you’re coming out of it," she said.

Cargill wondered briefly just what it was he was coming out of. Amnesia, certainly —temporary amnesia. The thought faded. To a man who had been unconscious several times now another spasm of darkness didn’t matter.

Here he was. That was what counted.

"Where are we going?" he asked and his voice was quite normal.

The girl’s voice oddly suggested she was shrugging. "Couldn’t leave you in the city," she said.

"Why not?"

"The Shadows would get you."

The phrase had a rhythm that snatched Cargill’s attention. The Shadows — will — get you. The Shadows will get you. He could almost imagine children being frightened by the threat.

His thought poised on the fact that at least one Shadow had seen him. He said as much. There was a pause. Then, "He’s not — one of them."

"Who is he?"

"He has a plan"— she hesitated — "for fighting them."

Cargill’s mind made a single, embracing leap. "Where do I fit into this plan?"

Silence answered. Cargill waited, then strode forward and fell in step beside her.

"Tell me," he said.

"It’s very complicated." She still did not turn her head. "We had to have somebody from a time far past so the Shadows couldn’t use their four-dimensional minds on him. He looked at you and said he couldn’t tell what your future was. Here and there through history are individuals who are — complicated — like that. You’re the one we selected."

"Selected!" Cargill exclaimed. Then he was silent. He had an abrupt impossible picture that everything that had happened to him had been planned. In his mind’s eye he saw a drunken soldier being selected to wreck a car and kill a girl. No, wait, that couldn’t be. He had got drunk that night deliberately. They couldn’t have had anything to with that.

The fury of his speculation subsided.

The possibilities were too intricate. With a cold intentness he stared at the shadowed profile of Ann Reece.

"I want to know," he said, "what way I’m supposed to be used."

"I don’t know," she said. "I’m only a pawn."

His fingers snatched at her arm. "Like heck you don’t know," he said roughly. "Where are you taking me?"

THE fingers of her other hand tugged futilely at his hand. She struggled a little. "You’re hurting my arm," she whimpered.

Cargill released her reluctantly. "You can answer my question."

"I’m taking you to a hiding place of ours. You’ll be told there what’s next." Her tone was reluctant.

Cargill pondered the possibilities and liked them less every second. A mysterious group intended to use him against beings they feared so violently that they had gone into remote history for somebody to fight their enemies.

"Look," he said frankly, "I don’t like this situation at all. I don’t think I’m going with you to this hiding place."

That did not seem to worry her. "’Don’t be silly," she said. "Where would you go?"

Cargill pondered that uneasily. Once in Germany his unit had withdrawn in disorder and he had been in enemy territory for two days. He could picture that a similar predicament here might be equally unhappy.

He looked down at himself, undecided. For some minutes, he had been aware that he had on clothes. In that dimness it was impossible to see what they were like but he felt warm and cozy. Surely, they wouldn’t have given him conspicuous clothing. Abruptly, he made up his mind.

"I don’t think," he said quietly, "that I’m going any farther in your direction. Good-by."

He stepped away from her and ran rapidly along the road, back the way they had come. After not more than ten seconds he plunged off the road and found himself scrambling through thick brush. Aim Reece’s flashlight flared behind him obviously seeking him. But the reflections from the beam only made it easier for him to penetrate the brush.

He broke into a meadow and trotted across it — and then he was in brush again. For the first time then he heard her voice calling, "You fool, you! Come back!"

For several minutes, her words broke the spell of the night but he heard only snatches now.

Once he thought she said, "Watch out for the Planiacs! But that didn’t make sense.

He passed over the crest of a hill and thereafter heard her no more.

PURPOSEFULLY though carefully Cargill pressed on through the darkness. He grew startled by the extent of the wilderness but it was important that he keep moving. In the morning there might be a search for him and he had better be as far as possible from the road where he had left Ann Reece.

The night was dark, the sky continued sullen. The tangy smell of water warned him that he was approaching either a river or a lake. Cargill turned aside. He was crossing what seemed to be an open space when, out of the night, the beam of a flashlight focused on him.

A girl’s high-pitched voice said, "Darn you, I’ve got my — on you." He didn’t get the word. It sounded like spitter. "Put up your hands."

In the reflections of the flashlight, Cargill glimpsed a dull metal gadget that looked like nothing else than an elongated radio tube. It pointed at him steadily.

The girl raised her voice in a yell. "Hey, pa, I’ve caught myself a —" The word sounded like wiener but Cargill rejected that. The girl went on excitedly, "Come on, pa, and help me get him aboard."

Afterwards, Cargill realized he should have tried to escape at that moment. It was the unnatural weapon that held him indecisive. Had it been an ordinary gun he’d have dived off into the darkness — or so he told himself when it was too late.

Before he could decide a roughly dressed man loped out of the darkness. "Good work, Lela," he said, "you’re a smart girl."

Cargill had a flashing glimpse of a lean, rapacious, bearded countenance. And then the man had taken up a position behind him and was jabbing another of the tube-like weapons into him.

"Get going, stranger, or I’ll spit you."

Cargill started forward reluctantly. Ahead of him a long, snub-nosed snub-tailed structure loomed up vaguely out of the darkness. The light from the flash seared across it, sending back glassy reflections. And then —

"Follow Lela through that door!’

There was no escape now. The man and the gun crowded behind him. Cargill found himself in a large dimly lighted room, amazingly well constructed and looking both cozy and costly. Then he was being urged across the carpeted floor, past a comfortable lounge into a narrow corridor and toward a tiny room that was even more dimly lighted than the first one.

A few moments later, while the man glowered in the doorway, the girl fastened a chain around Cargill’s right and left ankles. A key clicked twice, then she was drawing back, saying, "There’s a cot in that corner."

His two captors retreated along the corridor toward the brighter light, the girl babbling happily about having "caught one of them at last."

The man said, "Maybe we’d better cast adrift. Maybe there’s more of them."

The light in Cargill’s room went out. There was a jerk and then slow upward movement. Cargill thought, amazed, An airship!

His mind jumped back to what Ann Reece had shouted at him — "Watch out for the Planiacs!" Had she meant — this? Carefully, in the darkness he edged towards the cot the girl had indicated. He reached it and sank down on it wearily.

He spent about a minute fumbling over the chain with his fingers. The metal was hard, the chain itself just over a foot long, an excellent length for hobbling a man.

He was suddenly too tired to think about it. He lay down and must have slept immediately.

CHAPTER IV - Life with Lela

CARGILL had a lazy sensation of drifting along. For some reason he resisted waking up and kept sinking back into the darkness. Throughout that early dreamy stage he had no memory of what had happened or of where he was.

Gradually however he grew conscious of motion underneath him. He stirred and felt the chain clasps against his ankles. That jarred. That brought the beginning of alarm. With a start he woke up.

His eyes took in the curving metal ceiling, and all too swiftly he remembered. He reached down and touched the chain. It was cool and hard and convincing to his touch. It gave him an empty feeling.

And then, just as he was about to sit up, he realized he was not alone. He started to turn his head, caught a glimpse of what was there and barely in time brought his hands up in front of his face.

A whip cracked across his fingers, and licked at his neck with a flame-like intensity. "Get up you lazy good-for-nothing." The man who stood in the doorway was already drawing the whip back for another blow.

With a gasp Cargill swung his legs from the cot to the floor. In black rage he was about to launch himself at the other when the metallic rattle of the chain reminded him that he was desperately handicapped. That dimmed his fury and brought a sense of disaster.

Once more the whip struck at him. Cargill ducked and managed to get part of the blow on the sleeve of his coat. The thin sharp end flicked harmlessly past his shoulder against the metal wall.

Again the whip was drawn back.

He had already, blurrily, recognized his assailant as the man who had been with the girl the night before. Seen in the light of day he was a scrawny, slovenly individual about forty years old. Several days’ growth of beard darkened his face. His lips were thin.

His eyes had a curiously crafty expression and his face was a mask of bad temper. He wore a pair of greasy trousers and his filthy shirt, which was open at the neck, revealed a flat hairy chest.

He stood with an animal-like snarl on his face. "Darn your hide, get going!"

Cargill thought: If he tries to hit me again, I’ll rush him.

Aloud he temporized. "What do you want me to do?"

That seemed to add new fury to the man’s anger. "I’ll learn you what I want!"

The whip came up and it would have flashed down except for one thing. Cargill lunged from the cot and flung himself across the intervening space. The violent impact of their coming together nearly took his breath away but it smashed the other against the metal doorjamb.

He let out a screech and tried to pull back. But Cargill had him now. With one hand he clutched the man’s shirt. With the other hand, clenched, he struck at the thin, bony jaw.

It was a knockout. A limp body collapsed toward the floor. Cargill followed, kneeling awkwardly and with trembling fingers started to search the other’s pockets.

From farther along the corridor, the girl’s voice said, "All right, put up your hands or I’ll spit you."

Cargill jerked up, tensed for action. He hesitated as he saw the weapon, then reluctantly drew back from the man’s body. Stiffly, he sat down on the cot.

The girl walked forward, and dug the toe of her shoe into her father’s ribs.

"Get up, you fool," she said.

The man stirred, and sat up. "I’ll kill him," he mumbled. "I’ll murder that blasted —" It still sounded like wiener.

The girl was contemptuous. "You aren’t going to kill anybody. You asked for a kick in the teeth and you got it. What did you want him to do?"

The man stood up groggily, and felt his jaw. "These darn Tweeners," he said, "make me sick with their sleeping in, and not knowing what to do."

The girl said coldly, "Don’t be such a fool, Pa. He hasn’t been trained yet. Do you expect him to read your mind?" She squeezed past him, and came into the little room. "And besides, you keep your dirty hands off him. I caught him, and I’ll do any beating that’s necessary. Give me that whip."

"Look, Lela Bouvy," said her father, "I’m the boss of this floater and don’t you forget it." But he handed her the whip and said sullenly, "All I want is some breakfast and I want it quick."

"You’ll get it. Now beat it." She motioned imperiously. "I’ll do the rest."

The man turned and slouched out of sight.

The girl gestured with her thumb.

"All right, you, into the kitchen."

Cargill hesitated, half-minded to resist. But the word, kitchen, conjured thoughts of food. He realized he was tremendously hungry. Silently he climbed to his feet and hobbled clumsily through the door she indicated.

He was thinking, these creatures could keep me chained up here from now on.

The despair that came was like a weight, more constricting than the chain that bound him.

THE kitchen proved to be a narrow corridor between thick translucent walls. It was about ten feet long and at the far end was a closed transparent door, beyond which he could see machinery. Both the kitchen and the machine room were bright with the light that flooded through the translucent walls.

Cargill glanced around, puzzled. There was no sign of a stove or of any standard cooking equipment. He saw no food, no dishes, no cupboards. He looked for lines in the glass-like walls. There were hundreds, horizontal, vertical, diagonal, curving and circular. They seemed to have no purpose. If any of them marked off a panel or a door he couldn’t see it.

He turned questioningly to the girl. She spoke first. "No clouds this morning. We’ll be able to get all the heat we want."

He watched, interested, as she reached up with one hand, spread it wide and touched the top of the wall where it curved toward the ceiling. Only her thumb and little finger actually touched the glass. With a quick movement she ran her hand along parallel to the floor, lightly.

A thick slab of the glass broke free along an intricate series of lines and noiselessly slid down into a slot. Cargill craned his neck. From where he stood he could just see that there was a limpidly transparent panel inside, behind which were shelves. What was on the shelves, he could not see.

The girl slid the panel casually sideways. For a moment then her body hid what she was doing. She drew back holding a plate with raw fish and potatoes on it. It looked like trout, and surprisingly it had been cleaned. It was surprising to Cargill because neither Bouvy nor his daughter looked as if they were capable of doing anything in advance.

He shrewdly suspected the presence of kitchen gadgets that could scale and fillet a fish automatically.

The girl took a few steps toward him. Once more she ran her little finger and thumb along the upper wall. Another section of that sunlit wall slid down and there was a second panel with shelves behind it. The girl opened the panel, and placed the plate on one of the shelves.

As she closed the panel a faint steam rose from the fish. It turned a golden brown. The potatoes lost their hard whiteness, and visibly underwent the chemical change to a cooked state.

"That’ll do, I guess," said Lela Bouvy. She added, "You better get yourself a bite."

She took out the plate in her bare hands, paused at the refrigerator to take out an apple and a pear from a bottom shelf and walked out, still carrying the plate.

Cargill was left alone in the kitchen. By the time she returned for her own breakfast, he had eaten an apple, cooked himself some chicken legs and potatoes and was busily eating when she paused in the doorway.

SHE was rather a pretty thing if you allowed for a certain sullenness of expression. So it seemed to Cargill. Her hair was not too well combed but it was not tangled and it had a kind of a pleasant shine that showed some attention had been lavished on it.

Her eyes were a hot blue, her lips full and her chin came to a point. She wore dungarees and an open-necked shirt that partly exposed a very firm tanned bust.

She could have been very pretty.

She said, with a suspicious tone in her voice, "How did a smart-looking Tweener like you come to get caught so easy?"

Cargill swallowed a vast mouthful of potato in several quick gulps, and said. "I’m not a Tweener."

The hot blue of her eyes smoldered with easy anger. "What kind of a smarty answer is that?"

Cargill cleaned up what was left on the plate and said, "I’m being honest with you. I’m not a Tweener."

She frowned. "Then what are you?" She stiffened. The anger went out of her eyes. They seemed to change color. A fear blue, slightly but curiously different. She whispered, "Not a Shadow?"

Before he could pretend or even decide not to she answered her own question. "Of course, you aren’t. A Shadow would know all about this ship and how the kitchen works without having to watch me first. They fix our ships for us floater folk when the repair job is too big for us to figure out."

The moment for pretense, whatever its possibilities might have been, was past. Cargill said grudgingly, "No, I’m not a Shadow.’

The girl’s frown had deepened. "But a Tweener would’ve known that too." She looked at him warily, "What’s your name?"

"Morton Cargill."

"Where are you from?"

Cargill told her and watched those expressive eyes of hers change color again. Finally she nodded. "One of those, eh?" She seemed disturbed. "We get a reward for people like you."

She broke off, "What did you do — back where you came from — to start the Shadows after you?"

Cargill shrugged. "Nothing." He had no intention of launching into a detailed account of the Marie Chanette incident.

Once more, the blue eyes were flashing. "Don’t you dare lie to me," she said. "All I’ve got to do is to tell Pa that you’re a getaway and that’ll cook your goose."

Cargill said with all the earnestness he could muster, "I can’t help that. I really don’t know." He hesitated, then said, "What year is this?"

The moment he had asked the question he felt breathless.

CHAPTER V - A Woman’s Loud Voice

HE hadn’t thought about it before. He hadn’t had time. The clock in the glass-walled room in Shadow City had indicated that it was May 6th but not what year it was. Everything had happened too swiftly. Even his blurred questions to Ann Reece during those first minutes after her arrival had been so weighted with emotion that the possibilities of being here in the future hadn’t really penetrated.

Which future? What year? What had happened during the centuries that must have passed? Where? How? Who? He caught his whirling mind, fastened it down, brought it to focus. The most important fact was — what year?

Lela Bouvy shrugged, and said, "Two Thousand Three Hundred and Ninety-One."

Cargill ventured, "What I can’t understand is how the world has changed so completely from my time." He described the United States at the end of World War Two.

The girl was calm. "It was natural. Most people want to be free, not to have to live in one place or to be tied to some stupid work. The world isn’t completely free yet. We floater folk are the only lucky ones so far."

Cargill had his own idea of a freedom where the individuals depended on somebody else to repair their machines. But he was interested in information, not in exploding false notions.

He said cautiously, "How many floater folk are there?"

"About fifteen million."

She spoke glibly but Cargill let the figure pass.

"And the Tweeners?" he asked.

"Three million or so." She was contemptuous. "The cowards live in cities."

"What about the Shadows?"

"A hundred thousand, maybe a little more or less. Not much."

Cargill was left alone most of the rest of the day. He saw Lela briefly again when she came in and prepared lunch for herself and her father.

It was not till afternoon that he started to think seriously about what he had learned. The population collapse depressed him. It made the big fight of life seem suddenly less important.

All the eager ambition of the Twentieth Century was now proved valueless, destroyed by a catastrophe that derived not from physical force, but apparently from a will to escape responsibility. Perhaps the pressures of civilization had been too great. People had fled from it as from a plague the moment a real opportunity occurred.

IT was growing dark in the kitchen when Cargill realized the ship was sinking to a lower level. He didn’t realize just how low until he heard the metal shell under him whisk against the upper branches of trees.

A minute later there were a thud and a shock. The floater dragged for several feet along the ground, and then came to a stop. Cargill grew conscious of a muffled roaring sound outside.

Lela came into the room. Or rather, she walked straight through to the kitchen. Cargill had a sudden suspicion of what she planned to do and lurched to his feet. He was too late. The door of the engine room was open, and the girl was in the act of lowering a section of the glass wall.

As he watched she eased down a hinged section of the outer wall and ’stepped through out of sight. A damp sea breeze blew into Cargill’s face and now he heard the roar of the surf.

The girl came back after about a minute and paused in his room. "You can go outside if you want," she said. She hesitated. Then, "Don’t try to run away. You won’t get far, and Pa might burn you with a spit gun."

Cargill said ruefully, "Where would I run to? I guess you folks are stuck with me."

He watched her narrowly to see how she took that. She seemed relieved. It was not a positive reaction but it was suggestive. It fitted with his feeling that Lela Bouvy would welcome the presence of someone other than her father.

As he hobbled through the kitchen a moment later Cargill silently justified the plan he had of worming his way into the girl’s confidence. A prisoner in his situation was entitled to use every trick and device necessary to his escape.

He did not pause at the engine room door — how it opened, he would discover in the morning. He manipulated his chained legs down a set of steps — part of the outer wall folded out and down on hinges.

A moment later he stepped onto a sandy beach.

They spent most of the evening catching crabs and other sea creatures that crowded around a light that Bouvy lowered into the water. It was a wild seacoast, rocky except for brief stretches of sand. A primeval forest came down in places almost to the edge of the rock that overlooked the restless sea below.

Lela dipped up the tiny creatures with a little net and tossed them onto a pile where Cargill with his fingers separated the wanted from the unwanted. It was easy to pick out and throw back the ones that Lela pointed out as inedible, to toss the others into a pail.

Periodically, the girl took a pail-full of the delicacies back to the floater.

She was in a visible state of exhilaration. Her eyes flashed with excitement in the light reflections, her face was alive with color. Her lips parted, her nostrils dilated. Several times when Bouvy had moved farther along the beach and the sound of the surf prevented her father from hearing she shrieked at Cargill, "Isn’t it fun? Isn’t this the life?"

"Wonderful!" Cargill yelled hack. Once he added, "I’ve never seen anything like it."

That seemed to satisfy her and it was true up to a point. There was a pleasure to open-air living. What she didn’t seem to understand was that there was more to being alive than living outdoors. Civilized life had many facets, not just one.

SHE came into his part of the ship a dozen times the next day. Cargill, who had unsuccessfully sought the secret of how to open the engine-room door, finally asked her how it was done. She showed him without hesitation. It was a matter of touching both doorjambs simultaneously.

When she had gone Cargill headed straight for the engine room, paused for a moment to study the engine — that proved a futile process, since it was completely closed in —and then slid the wall section into the floor and looked down at the world beneath.

The world that sped by below was a wilderness, but a curious sort. As far as the eye could see were the trees and shrubbery associated with land almost untouched by the hand and metal of man. But standing amid weeds and forests were buildings.

Even from a third of a mile up those that Cargill saw looked uninhabited. Brick chimneys lay tumbled over on faded roofs. Windows seen from a distance yawned emptily, or gazed up at him with a glassy stare. Barns sagged unevenly and here and there the wood or brick or stone had completely collapsed and the unpainted ruin drooped wearily to the ground.

In the beginning the only structures he saw were farmhouses and their outbuildings. But abruptly a town flowed by underneath. Now the effect of uninhabited desolation was clearly marked — tottering fences, cracked pavement, overgrown, lay weeds and the same design of disintegration in the houses.

When they had passed over a second long-abandoned town Cargill closed the panel that had concealed the window, and returned uneasily to his cot.

Coming as he did from a world in which virtually every acre of tillable land was owned and used by somebody, he was shocked by the way vast areas had been allowed to revert to a primitive state. He tried to picture from what the girl had told him and from what he had observed how it might have happened. But that got him nowhere.

He wondered if the development of machinery had finally made agriculture unnecessary. If it had, then this was still a transition stage. The time would come when these ghost farms and ghost towns and perhaps ghost cities would I return to the soil from which they had, in their complex fashion, sprung. The time would come when these costly monuments of an earlier civilization would be as gone and forgotten as the cities of antique times.

They spent two more evenings fishing. On the fourth day Cargill heard a woman’s loud voice talking from the living room. It was an unpleasant voice and it startled him.

Curiously he had never thought of these people as being in communication with anyone else. But the woman was unmistakably giving instructions to the Bouvy father and daughter. Almost as soon as she had stopped talking Cargill felt the ship change its course. Toward dark Lela came in.

"We’ll be camping with other people tonight," she said. "So you watch yourself." She sounded fretful and she went out without waiting for him to reply.

Cargill considered the possibilities with narrowed eyes. After four days of being in hobble chains, with no sign that they would ever come off, he was ready for a change.

"Basically, all I’ve got to do," he told himself, "is catch two people off guard." And he wouldn’t have to be gentle about it either.

"Careful," he thought. "Better not build my hopes too high."

Nevertheless, it seemed to him that the presence of other people might actually produce an opportunity for escape.

CHAPTER VI – Carmean

THROUGH the open doorway Cargill caught glimpses of the outside activity. Men walked by carrying fishing rods. The current of air that surged through brought the tangy odor of river and the damp pleasant smell of innumerable growing things.

It grew darker rapidly. Finally Cargill could stand it no longer. He stood up and, taking care not to trip over his chain, went outside and sank down on the grass.

The scene that spread before him had an idyllic quality. Here and there under the trees ships were parked. There were at least a dozen that he could see and it seemed to him that the lights of still others showed through the thick foliage along the shore. The sound of voices floated on the air and somehow they no longer sounded harsh or crude.

There was a movement in the darkness near him. Lela Bouvy settled down on the grass beside him. She said breathlessly, "Kind of fun living like this, isn’t it?"

Cargill hesitated and then, somewhat to his surprise, found himself agreeing.

"There’s a desire in all of us," he thought, "to return to nature."

The will to relax, the impulse to lie on green grass, to listen to the rustling of leaves in an almost impalpable breeze — all that he could feel in himself. He also had the basic urge that hail driven these Planiacs to abandon the ordered slavery of civilization. He found himself saddened by the realization that the abandonment included a return to ignorance.

He said aloud, "Yes, it’s pretty nice."

A tall powerful-looking woman strode out of the darkness. "Where’s Bouvy?" she said. A flashlight in her hand winked on and glared at Lela and Cargill. Its bright stare held steady for seconds longer than was necessary.

"Well, I’ll be double darned," the woman’s voice said from the intense blackness behind the light, "little Lela’s gone and found herself a man."

Lela snapped, "Don’t be a bigger fool than you have to be, Carmean,"

The woman laughed uproariously. "I heard you had a man," she said finally, "and now that I get a look at him I can see you’ve done yourself proud."

Lela said indifferently, "He doesn’t mean a thing to me."

"Yeah?" said Carmean derisively. Abruptly she seemed to lose interest. The beam of her flashlight swept on and left them in darkness. The light focused on Pa Bouvy sitting in a chair against the side of the ship. "Oh, there you are," said the woman.

"Yup!"

The big woman walked over. "Git up and give me that chair," she said. "Haven’t you got no manners?"

"Watch your tongue, you old buzzard," said Bouvy pleasantly. But he stood up and disappeared into the ship. He emerged presently with another chair.

During his absence the woman had picked up the chair in which he had been sitting and carried it some twenty-five feet along the river’s bank.

She yelled at Bouvy, "Bring that contraption over here! I want to talk to you privately. Besides, I guess maybe those two love-birds want to be alone." She guffawed.

Lela said in a strained voice to Cargill, "That’s Carmean. She’s one of the bosses. She thinks she’s being funny when she talks like that."

Cargill said, "What do you mean, one of the bosses?"

The girl sounded surprised. "She tells us what to do." She added hastily, "Of course, she can’t interfere in our private life."

CARGILL digested that for a moment. During the silence he could hear Carmean’s voice at intervals. Only an occasional word reached him. Several times she said, "Tweeners" and "Shadows." Once she said, "It’s a cinch."

There was an urgency in her voice that made him want to hear what she was saying but presently he realized the impossibility of making sense out of stray words.

He relaxed and said, "I thought you folks lived a free life? Without anybody to tell you what to do and where to get off."

"You got to have rules," said Lela. "You got to know where to draw the line. What you can do and what you can’t do." She added earnestly, "But we are free. Not like those Tweeners in their cities." The last was spoken scornfully.

Cargill said, "What happens if you don’t do what she says?"

"You lose the benefits."

"Benefits?"

"The preachers won’t preach to you," said Lela. "Nobody gives you food. The Shadows won’t fix your ship." She added casually, "And things like that."

Cargill whistled softly under his breath. The power of the church of the Middle Ages couldn’t have been any greater. This was excommunication with a capital E and ostracism in a rather ultimate fashion.

He said a. last, "So even the Shadows recognize her authority. Why?"

"Oh, they just want us to behave."

But you can capture Tweeners?"

The girl hesitated. Then, "Nobody seems to worry about a Tweener," she said.

Cargill nodded. He recalled his attempts to get information from her during the past few days. Apparently she hadn’t even thought of these restraining influences on her life. Now, though she seemed unaware of it, she had given him a picture of an incredibly rigid social structure.

Surely, he thought desperately, surely he could figure out some way to take ad-vantage of this situation. He moved irritably and the chain rattled, reminding him that all the plans in the world could not directly affect metal.

Carmean brought her chair back to the ship, closely followed by Bouvy. She set it down and then walked slowly over and stood in front of Cargill. She half-turned and said, "I could use a husky guy around, Bouvy."

"He isn’t for sale." That was Lela, curtly.

"I’m speaking to your Pa, kid, so watch your tongue."

"You heard the girl," said Bouvy. "We’ve got a good man here." His tone was cunning, rather than earnest. He sounded as if he were prepared to haggle but wanted the best of the deal.

Carmean said, "Don’t you go getting commercial on me." She added darkly, "You’d better watch out. These Tweeners haven’t got any religion when it comes to a good-looking girl."

Bouvy grunted but when he spoke he still sounded good-humored. "Don’t give me any of that. Lela’s going to stick with her Pa and be a help to him all her life. Aren’t you, honey?"

"You talk like a fool, Pa. Better keep your mouth shut."

"She’s fighting hard," said Carmean slyly. "You can see what’s in the back of her mind."

Bouvy sat down in one of the chairs. "Just for the sake of the talk, Carmean," he said, "what’ll you give for him?"

Cargill had listened to the early stages of the transaction with a shocked sense of unreality. But swiftly now he realized that he was actually in process of being sold.

It emphasized, if emphasis was needed, that to these Planiacs he was a piece of property, a chattel, a slave who could be forced to menial labor or whipped or even killed without any one being concerned. His fate was a private affair that would trouble no one but himself.

"Somebody’s going to get gypped," he told himself angrily. A man as determined as he was to escape would be a bad bargain for Carmean or anyone else. In the final issue, he thought, he’d take all necessary risks and he had just enough front-line army experience to make that mean something.

THE bargaining was still going on. Carmean offered her own ship in return for Cargill and the Bouvy ship. ’It’s a newer model," she urged. "It’s good for ten years without any trouble or fussing."

Bouvy’s hesitation was noticeable. "That isn’t a fair offer," he said plaintively. "The Shadows will give you all the new ships you want. So you aren’t offering me anything that means anything to you."

Carmean retorted, "I’m offering you what I can get and you can’t."

"It’s too much trouble," said Bouvy. "I’d have to move all our stuff."

"Your stuff!" The big woman was contemptuous. "Why, that junk isn’t worth carting out! And besides, I’ve got a ship full of valuables over there."

Bouvy was quick. "It’s a deal if you change ship for ship with everything left aboard."

Carmean laughed curtly. "You must take me for a bigger fool than I look. I’ll leave you more stuff than you’ve ever seen but I’m taking plenty out."

Lela, who had been sitting silently, said, "You two are just talking. It makes no difference what you decide. I caught him and he’s mine. That’s the law and you just try to use your position as boss to change it, Carmean."

Even in the darkness, Carmean’s hesitation was apparent. Finally she said, "We’ll talk about this some more tomorrow morning. Meantime, Bouvy, you’d better teach this kid of yours some manners."

"I’ll do just that," said Pa Bouvy and there was a vicious undertone in his voice. "Don’t you worry, Carmean. You’ve bought yourself a Tweener and if we have any trouble in the morning there’s going to be a public whipping here of an ungrateful daughter."

Carmean laughed in triumph. "That’s the kind of talk I like to hear," she said. "The old man’s standing up for himself at last."

Still laughing, she walked off into the darkness. Pa Bouvy stood up.

"Lela!"

"What?"

"Get that Tweener inside the ship and chain him up good."

"Okay, Pa." She climbed to her feet. "Get a move on," she said to Cargill.

Without a word, moving slowly because of the chain, Cargill went inside and lay down on his cot.

It must have been several hours later when he awoke, aware that somebody was tugging at the chain.

"Careful," whispered Lela Bouvy, "I’m trying to unlock this. Hold still."

Cargill, tense, did as he was told. A minute later he was free. The girl’s whisper came again, "You go ahead — through the kitchen. I’ll be right behind you. Careful."

Cargill was careful.

CHAPTER VII - Shadow Man

CARGILL lay in the dark on the grass with no particular urge to move. The feel of being free had not yet taken firm root inside him. The night had become distinctly cooler and most of the machines were dark. Only one ship still shed light from a half-open doorway and that was more than a hundred feet along the river bank from where he crouched.

Cargill considered his first move. More quickly now he began to realize his new situation. He need only creep out of this camp and then go where he pleased. At least it seemed for a moment as if that was all he had to do. He felt reluctant actually to do it.

In the darkness progress would be difficult and morning might find him still dangerously close to the Planiacs. He imagined himself being seen from the air. He pictured a search party with an air support, finding him within a few hours after dawn. The possibilities chilled him and brought the first change in his purpose.

"If I could steal one of these ships," he thought indecisively.

There was a faint sound beside him and then the whispered voice of Lela Bouvy said, "I want you to take her ship. That’s the only way I’ll let you go."

Cargill turned in the darkness. Her words implied that she had a weapon to force him to do what she wanted. But the darkness under the trees was too intense for him to see if she were armed. He didn’t have to be told that "her ship" referred to Carmean’s. His response must have been too slow, Once more Lela spoke.

"Get going."

Carmean’s ship was as good as any, Cargill decided. He whispered, "Which is hers?"

"The one that’s got a light."

"Oh!"

Some of his gathering determination faded. Carmean asleep and Carmean awake were two different propositions. In spite of his qualms he began to move forward. There was such a thing as investigating the situation before making up his mind. A few minutes later he paused behind a tree about a dozen feet from Carmean’s ship.

The dim light that streamed from the partly open doorway made a vague patch of brightness on the grass. Near the edge of that dully-lighted area Carmean herself sat on the grass.

Cargill, who had been about to start forward again, saw her just in time. He stopped with a gulp and it was only slowly that the tension of that narrow escape left him. He glanced back finally and saw Lela in the act of moving toward him. Hastily Cargill headed her off.

He drew her into the shelter of a leafy plant, explained the situation, and asked, "Is there anybody else in the ship?"

"No. Her last husband fell off the ship three months ago. At least that was what Carmean said happened. She’s been looking for another one ever since but none of the men’ll have her. That’s why she wanted you."

It was a new idea to Cargill. He had a momentary mental picture of himself in the role of a chained husband. It shocked him. He could feel himself stiffening to the necessities of this situation.

The sooner he got away from these people, the better off he’d be. And in view of their casually ruthless plans for him he need feel no sense of restraint.

He whispered to Lela, "I’ll jump on her and bang her over the head. Have you got anything I can hit her with?" He felt savage and merciless. He hoped the girl would give him her gun. Just for an instant then, as she slipped something metallic into his hand, he thought she had done so.

She whispered fiercely, "That’s from the edge of your cot. It’ll look as if you got free and took it along as a weapon."

The logic of that was not entirely convincing to Cargill but he saw that she was trying to convince herself. And it was important that there be some kind of explanation for his escape. Bouvy would undoubtedly be furious with her.

Cautiously Cargill stole forward. As he reached the shelter of the tree near Carmean the big woman climbed heavily to her feet.

"So you finally got here, Grannis," she said to somebody Cargill couldn’t see.

"Yes," said a voice from the other side of the tree behind which Cargill crouched, rigid now. The man’s voice went on, "I couldn’t make it any sooner."

"So long as you could make it at all," said Carmean indifferently. "Let’s go inside."

Just what he expected then, Cargill had no idea. He had a brief, bitter conviction that he ought to attack both the stranger and Carmean and then —

A Shadow walked into the lighted area.

MORTON CARGILL stayed where he was, behind the tree. His first feeling of intense disappointment yielded to the realization that there was still hope. This was a secret midnight meeting. The Shadow who had come to talk to Carmean would leave presently and there’d be another opportunity to seize the ship.

He started cautiously to back away and then he stopped. It seemed to him suddenly that perhaps he ought to overhear what was being said. He was planning how he would do it when Lela slipped up behind him.

"What’s the matter?" she whispered angrily. "Why are you standing there?"

"Sh-h-h-h!" said Cargill. That was almost automatic. He was intent on his own purposes, acutely conscious now that anything that concerned the Shadows could concern him.

"I’ve got to remember," he told himself, "that I was brought here by someone who intended to use me."

His capture by Lela was an unfortunate incident not on the schedule of the original planners. He paid no attention to the girl but slipped from behind the tree and headed for Carmean’s floater. He reached the door safely and flattened himself against the metal wall beside it.

Almost immediately, he had his first disappointment. The voices inside were too far away for him to hear. As had happened when Carmean talked to Pa Bouvy earlier, only occasional words came through.

Once, a man’s voice said, "The attack must be carefully timed."