Home > A. E. van Vogt > THE 83 VAN VOGT STORIES ON THIS SITE > "Abdication" by A. E. van Vogt and E. M. Hull (1943)

"Abdication" by A. E. van Vogt and E. M. Hull (1943)

"Abdication" by A. E. van Vogt and E. M. Hull (1943)

Saturday 17 June 2023, by

Two very rich and very adventurous adventurers get mixed up in a violent intrigue involving huge mining rights on a faraway planet, and try to survive the complications that ensue with the aid of a new-fangled invisibility suit.

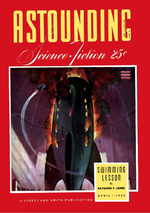

A golden-age space-opera kind of story with good pace and a neat twist at the end, that was initially published under the name of van Vogt’s wife E. Mayne Hull in the April 1943 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction , but that was credited to both A. E. van Vogt and E. Mayne Hull in all of the van Vogt anthologies in which it was republished during van Vogt’s lifetime.

However van Vogt may possibly have written this story himself, as the recently-published letters between van Vogt and John Campbell, the editor of Astounding, clearly imply that van Vogt did use his wife’s name as a pen-name during the forties – as Campbell did himself during his career as a writer – as a way to publish more than one story in the same issue of a magazine, contrary to the rules then in place.

This possibility is strengthened by the fact that the issue of Astounding in which it first appeared also contained a work by A. E. van Vogt [1]. That was also the case of the previous story ascribed to E. Mayne Hull published on this site, The Flight that Failed, that appeared in the December 1942 edition of Astounding in which there was also a story by A. E. van Vogt [2]. And it is undeniable that the quasi-superman qualities of the narrator in this tale closely follow the propensities of Mr. V to imagine the future development of mankind to head in that direction: we think here of works of the same period such as the novels Slan and The Voyage of the Space Beagle, and stories like The Monster and the Weapon Shop series.

However further investigation has shown that not all of E. Mayne Hull’s stories were published simultaneously with those of her husband, so joint authorship of works signed by both of them, such as this story, remains as the most likely explanation of their authorship.

(5,800 words)

An e-book is available for downloading below.

ABDICATION

The big man came aboard the space liner from one of the obscure planets in that group of stars known as the Ridge. The Ridge is not visible as such from Earth. It lies well to the ’upper’ edge of the Milky Way; and the long, jerky line of stars that compose it point at Earth, thus showing as a little, bright cluster in an Earth telescope. Seen from Kidgeon’s Blackness, far to the right, the Ridge stands out beautifully clear, one of the more easily distinguishable guidemarks in our Galaxy.

The area is not well serviced. Once a week an interstellar liner flashes down the row of stars, stopping off according to advance notices received from its agents on the several score little-known planets. On reaching the edge of the Ridge, the ship heads for the central communication centre, Dilbau III, where transfer is made to the great ships that traffic to distant Earth.

The entire trip requires about three weeks; and anyone who moved around as much as I did, soon learned that the most interesting part of the journey is watching the passengers who get on and off at the way ports.

That’s how I came to see the big man as soon as I did. Even before he came aboard from the surface craft that had flashed up to where we lay about a hundred thousand miles above the planet, I could see that the new passenger was somebody.

It was his luggage, case after case of it being hoisted by the cranes, which gave that information. Beside me, a ship’s officer gasped to a fellow officer:

’Good heavens, that’s ninety tons of the stuff so far!’ That made me straighten up with interest. They don’t allow freight on these liners; and ninety tons makes up a lot of personal belongings. The officer spoke again:

’It’s the permanent move, looks like to me. Somebody’s made his pile, and he’s going home to Earth. Look! It’s Jim Rand.’

It was.

I have a little theory of my own about legendary men of space like Jim Rand. It’s their reputations that enable them to accomplish their greatest and most widely publicized coups.

Initial momentum is necessary, naturally, and boundless energy and courage, but that only makes millions. It’s reputation that pushes such men into the billion stellor class.

Jim Rand’s deep, familiar voice broke my reverie: ’Hello, there,’ he said. ’I believe I know you, but I can’t place you.’ He had stopped a few feet from where I stood, and was staring at me.

He was a man of about fifty, with a small moustache, and a nose that looked as if it had been broken, and then repaired under emergency conditions. That slight twist in it didn’t hurt his looks any, rather it added a curious strength to the muscular lines of his face. His eyes were blue-green, bright now with puzzlement.

I knew exactly how he was feeling. People whom I’ve met, and meet again later, always wonder whether or not they know me; and sometimes they become very exasperated with their memories. It’s up to me, then, to recall the occasion. Sometimes, I do that; sometimes I don’t.

I said now: ’Yes, Mr Rand, I was introduced to you by a mutual friend when you were organizing the Wild Mines of Guurdu. Your mind was probably on more weighty matters at the time. My name is Delton – Chris Delton.’

His gaze was curiously steady. ’Maybe,’ he said finally. ’But I don’t think I’d forget a man of your appearance.’ I shrugged. They always say that. I saw that his face was clearing.

’Will you meet me in the lounge in about an hour?’ he said. ’Perhaps we can talk.’

I nodded. ’Happy to.’

I watched him walk off along the brilliantly lighted corridor, redcaps wheeling several trunks and bags after his tall, powerful form.

He did not look back.

Beneath my feet I could feel the shudder of engines. The great ship was getting under way.

"Yes,’ said Jim Rand an hour and a half later, ’I’m through, I’m retiring, quitting for good. No more wildcat stuff. I’ve bought an estate; I’m going to get married, have some children and settle down.’

We were sitting in the lounge, and we had become more friendly than I had thought possible. The great, glittering room was practically deserted, nearly everybody having answered the first call for dinner.

I said: ’I don’t wish to seem a cynic, but you know the old story: All this out here, these untamed planets, the measureless wealth, the dark vastness of space itself – it’s supposed to get into a man’s blood.’

I finished as coolly as I could: ’Actually, the most important thing in your life at the moment is that at least two, possibly four, men have been watching you for the past three minutes."

’Yes,’ said Jim Rand. ’I know. They’ve been there since we came in.’

’Do you know them?"

’Never saw them before in my life.’ He shrugged. ’And I don’t give a damn either. Five years ago, even last year, I might have got myself excited about the possibilities. Not now. I’m through. My mind is made up. I’ve laid my plans.’

He settled back in the lounge chair, a big, alert man, smiling at me with a faint, amused expression in his eyes. ’I’m glad you were aboard,’ he said, "though I still can’t remember our last meeting. It would have been boring alone with all these little minds."

He waved a great hand with a generous gesture that took in half the ship. I couldn’t suppress a smile. I said:

’Boredom – there’ll be plenty of that on Earth for a man of action. The place is closed in by the damnedest laws – all kinds of queer regulations about not carrying energy guns – and if anybody bothers you, or starts trouble, you’ve got to settle it in court. Why, do you know, they sentence you to jail simply for owning an invisibility suit?’

Rand smiled lazily. ’That won’t bother me. I gave all mine away.’

I stared at him, frowning. ’You know,’ I said finally, ’I’ve found that trouble never asks whether it’s welcome or not.

Don’t look now, but somebody’s just got out of the elevator, and is coming towards you.’

I finished: ’If you need any help, just call on me.’

"Thank you,’ said Jim Rand. He smiled his lazy smile, but I could see the gathering alertness in him. ’I usually handle my own trouble.’

It was I who had the vantage point. I was facing the elevator. Rand was sitting sidewise to it; and, superb actor that he was, he did not deign to glance around, or so much as flick an eyelash.

I studied the stranger who was approaching without looking at him directly. His eyes, I saw, were dark in colour, rather close-set behind a long, thin nose. It was a wolfish face thus set off, with thin, cruel lips and a receding chin that yet gave no suggestion of weakness. The man eased his lank body into the lounge beside Rand.

Ignoring me, he said: ’We might as well understand each other.’

If Rand was startled by that, there was no indication on his face. He smiled, then pursed his lips.

’By all means,’ he said. ’Misunderstandings are bad, bad.’ He clicked his tongue sadly, as if the memory of past misunderstandings and resultant tragedies was passing through his mind. It was magnificently done, and I could not restrain a thrill of admiration.

’You are meddling in something which is no business of yours.’

Rand nodded thoughtfully to that, and I could see that the movement was more than an actor’s gesture. It must be occurring to him by now that he had better put some thought to such an open threat.

His voice was light, however, as he said: ’Now, there, you have touched on one of my pet subjects – business ethics.’

The man’s dark-brown eyes flamed. He spat his words: ’We have already been compelled to kill three men. I am sure, Mr Blord, you would not want to be the fourth."

That startled Rand. His eyes widened; and there was no doubt that he was shocked at the discovery that he was being mistaken for someone else, particularly that someone.

I don’t know whether I’m qualified to speak about Artur Blord. He’s simply one of several dozen similar types of men who made the Ridge their stamping ground. Cities spring up where the heavy hand of their money points. And that brings more money, which they concentrate elsewhere.

Blord differed from the others only in that he was a mystery, and few people had ever seen him. For some reason this added to his reputation, so much so that I have heard people speak about him in hushed whispers.

The shock faded from Rand’s face. His eyes narrowed. He said coldly:

’If there must be a fourth dead man, I assure you it won’t be me.’

The wolf-face man actually changed colour. That’s what reputation can do. He said hastily, his tone conciliatory.

"There’s no reason for us to be fighting. There’re nine of us now, all good men that even you, Blord, cannot afford to antagonize. I should have known I couldn’t scare you. Here’s our real proposition:

’We’ll give you ten million stellors, payable in cash, within an hour, provided you sign an agreement stating that you will NOT get off this ship tomorrow at Zand.’

He leaned back. ’Now, isn’t that a fair and square offer?’

’Perfectly,’ said Rand, emphatically, ’perfectly fair.’

"Then you’ll do it!’

’No!’ said Jim Rand. And moved his right arm about a foot. It was a long distance for that powerful arm to gather momentum; and its effect was comparatively devastating.

’I don’t like,’ said Jim Rand, ’people who threaten me.’ The man was moaning, clutching at his broken nose. He stumbled blindly to his feet and headed for the elevator. His four companions gathered around him, and they all vanished into the glistening interior.

As soon as the elevator door closed, Rand whirled on me. ’Did you get that?’ he said.’ he said. ’Blord! Artur Blord is mixed up in this. Do you realize what it could mean? He’s the biggest operator on this side of Dilbau III. He’s got a technique for using other men that’s absolutely the last word. I’ve always wanted to stack up against him but – ’ He stopped, then hissed: ’Wait here!’

He walked swiftly towards the elevator, stood for a moment staring at the floor indicator of the machine the others had taken, then climbed into the adjoining lift. Ten minutes later he settled softly in the seat he had left.

’Have you ever seen a wounded nid?’ he said exultantly. ’It heads straight for home without regard to the trail it may leave.’

There was bright fire in his gaze, as he went on briskly: "The chap whom I hit is called Tansey; and he and his gang have taken Apartments three hundred to three-oh-eight. The outfit must be new to the Ridge stars. Proof is they mistook a person as well known as I am for Blord. They – ’ Rand stopped short there. He looked at me sharply. ’What’s the matter?’

’I’m thinking,’ said I, ’of a man who’s retiring; his plans are all made, estate, wife, children – ‘

’Oh!’ said Jim Rand.

The glow faded from his eyes. Some of the life went out of him. He sat very still, frowning; and I didn’t have to be a mind reader to see the struggle that was taking place in his mind.

At last, he laughed ruefully, ’I am through,’ he said. ’It’s true I forgot myself for a moment, but I must expect occasional lapses. My will remains unalterable.’

He paused; then: ’Will you have dinner with me?’

I said: ’I had dinner served in my apartment before I came to meet you.’

’Well, then,’ he persisted, ’how about coming up to my rooms a couple of hours from now?’ He smiled. ’I can see you’re sceptical about me, and so you may be interested in proof that I’m really in earnest. I’ve got the presidential suite, by the way. Will you come?’

’Why, sure,’ I said. I sat watching him walk off towards the dining room.

It was half past eight – all these stellar ships are operated on Earth time – when Rand opened the door for me, and led me into his living-room. The whole room was littered with three-dimensional maps, each in its long case; and I was familiar enough with the topography that was visible to recognize the planet Zand II.

Rand looked at me quickly, laughed and said: ’Don’t get any wrong ideas. I’m not planning anything. I’m merely curious about the situation on Zand.’

I looked at him carefully. He had seated himself; and he seemed at ease, casual, without a real worry in him. I said, finally:

’I wouldn’t dismiss the matter as readily as that. Remember, you didn’t invite their attention in the first place; they’re not liable to wait for future invitations, either.’

Rand waved an impatient arm. "To hell with them. They’ll be off the ship in fifteen hours.’

I said slowly: ’You may not realize it, but your position in relation to such men is different than it’s ever been. For the first time in your existence, you’re thinking in terms of your personal future. In the past, death was an incident, and, if necessary, you were ready to accept it. Wasn’t that the general philosophy?

Rand was scowling: ’What are you getting at?’

"You can’t afford to take any chances. I’m going to suggest that I go to Apartment three hundred, and tell them who you are.’

Rand’s gaze was suspicious. ’Are you kidding?’ he said. ’Do you think I’m going to eat dirt for a bunch of cheap crooks? If I have to handle them, I’ll do it my way.’

He shrugged. ’But never mind. I can see you mean well. Take a look at this, will you?’

He indicated one of the long map plates, on which showed a section of the third continent of the planet Zand II. His finger touched a curling tongue of land that jutted into the Sea of Iss. I nodded questioningly, and he went on:

’Last time I was on Zand, they were building a city there. It was mostly tents, with a population of about a hundred thousand, about three hundred murders a week, and atomic engineering was just coming in. That was six years ago.’

’I was there last year,’ I said. "The population then was a million. There are twenty-seven skyscrapers of fifty to a hundred storeys, and everything was built of the indestructible plastics. The city is called Grenville after – ‘

Rand cut me off grimly. ’I know him. He used to work for me, and I had a run-in with him when I was on Zand. Had to leave fast at the time because I was busy elsewhere and because he had the power.’

A thoughtful frown creased his face. ’I always intended to go back.’

I nodded. ’I know. Unfinished business.’

He started to nod to that. And then he sat up and stared at me, I was absolutely amazed at the passion that flared in his voice, as he raged:

’If I went around finishing up all the business I’ve started and paying off all the ingrates, I’d still be here a thousand years from now.’

His anger faded. He looked at me sheepishly. ’I beg your pardon.’

There was silence. Finally, Rand mused: ’So there’re a million people there now. Where the devil do they all come from?’

’Not on these liners,’ I said. ’It’s too expensive. They come packed into small freighters, men and women crowded together in the same rooms.’

Rand nodded. ’I’d almost forgotten. That’s the way I came. You’d think it was romantic to hear some people talk. It’s not. I’ve had my skinful of frontier stuff. I’m settling in one of the garden cities of Earth in a fifteen-million-stellor palace with a wife that will – ’

He broke off. His eyes lighted. "That’s what I want to show you,’ he said. ’My future home, my future wife.’ Rand led the way into the second sitting-room – the lady’s sitting-room, it’s called in the circulars – and I saw with surprise that he had had a screen fitted up against a wall and there was a compact projector standing on the table.

Rand switched off the lights and turned on the projector. A picture flashed on the screen, the picture of a palatial house.

The first look made me whistle. I couldn’t help it. They say that men don’t dream of homes, but if ever anything looked like a dream come alive, this was it. There was a flow in the design, and a sense of space. I can’t just describe that. The mansion actually looked smaller than it was; it seemed like a jewel in its garden setting, a white jewel glittering in the sun.

There was a click; the picture faded from the screen, and Rand said slowly:

"That’s the house, built, paid for, fully staffed. Am I committed, or am I not?"

In the half darkness, I said: ’It can’t possibly cost more than a million stellors a year to maintain. Say, another million to operate a space yacht and to cover the overheads of watching your holdings. Your share of the Guurdu Mines alone will pay for it all ten times over.’

A light blinked on; and I saw that Rand was glaring at me. ’You’re hard to convince,’ he said.

’I know the hold,’ I said, "that the Ridge stars get on a man.’

He leaned back, relaxing. ’All right, I’ll admit everything you say. But I’m going to show you something now that you can’t set up against a money value.’

He reached towards a table on which lay some X-ray plates. I had noticed them before. Now, Rand picked up the top one and handed it to me. It was of a woman’s spine. Beside it, on the plate was written in some species of white ink:

Dear Jim:

The most perfect spine I have ever seen in a woman. When you consider that her IQ is 140, the answer is: don’t let her get away. With the right father, her children will all be super.

KARN GRAYSON, M.D.

"It that the woman?" I asked.

"That’s she.’ I could see that he was looking at me sharply, studying my face. ’I’ve got more plates here, but I’m not going to show them to you. They simply prove that she’s physically perfect. I’ve never met her personally, of course. My agents advertised discreetly, and among all the trashy women who answered was this marvel.’

In my life, in conversation with strong men, I’ve never been anything but frank. ’I’m wondering,’ I said steadily, "about the kind of woman who sends her specification like a prize animal.’

’I wondered about that, too,’ said Jim Rand. ’But I’ll show you.’

He did.

There will always be women like Gady Mellerton, I suppose, but not many. They’re scattered here and there through time and space; and each time the mould is destroyed, and must be painstakingly re-created. Invariably, they know their worth, and have no intention of wasting themselves on little men.

On the screen, she seemed tall, about five feet six, I judged. She had dark hair and – distinction. That was the essence of her appearance. She looked the way a queen ought to look and never does.

Her voice, when she spoke, was a golden, vibrant music: ’All I’ve seen of you, Jim Rand, is a picture your agent gave me. I like your face. It’s strong, determined; where you are you’re a man among men. And you don’t look dissipated. I like that, too.

’I don’t like being up here, parading myself like a show horse. I don’t like those X-rays that I had to have taken, but even in that I can appreciate that, far away as you are, you must set up standards and judge by them. I’m supposed to describe my life, and I like that least of all.’

Click! Rand cut off the voice, leaving the picture. ’I’ll tell you the rest,’ he said.

He told me about her, as I sat there unable to unloose my gaze from the screen.

’She’s a multi-operator. That’s one of those damn jobs out of which you can’t save any money. I don’t mean that the salary isn’t good. But they grab a piece out of it for old age insurance, for sickness, for compulsory holidays, and so much for clothes a year, so much for housing, entertainment. You’ve got to live up to your income. You know the kind of stuff.

’For the people as a whole, it’s paradise, a dream come true, but the only way a woman can break out of it is to marry somebody. Actually, when a first-rater gets caught in one of those perfect jobs, she’s sunk. It’s the purest form of slavery. It’s hell with a capital H. Can’t you just picture it?’

I said nothing. I sat there looking at the woman on the screen. She was about twenty-five; and I could picture her going to and from work, on her holidays, swimming. I could picture the beautiful children she would have.

I grew aware that Rand was pacing the floor. He seemed to realize my unqualified approval, for he was like a little boy who has shown off a new, remarkable toy. He glowed. He grinned at me. He rubbed his hands together.

’Isn’t she wonderful?’ he said. ’Isn’t she?’

I said at last, slowly: ’So wonderful that you can’t afford to take any chances with her future. So wonderful that I’m going to loan you an invisibility suit, and you’re going to sleep on the floor tonight.’

Rand paused in his pacing, confronted me. "There you go again,’ he scoffed. ’What do you think I am, a little sissy? I’m not hiding from anybody.’

His arrogance silenced me. If I had been asked at that moment whether Jim Rand was heading straight for Earth, my answer would have been an unqualified ’yes.’

It was an hour later when we separated, and nearly two hours after that when my doorbell sounded. I answered at once. Jim Rand stood there.

He looked startled when he saw that I was fully dressed. ’I thought you’d be in bed,’ he said, as I shut the door after him.

’What’s the matter?’ I asked. ’Anything happen?’

’Not exactly.’ He spoke, and he did not look straight at me. ’But after I went to bed I realized that I’d been very foolish.’

My mind leaped instantly to the girl, Gady Mellerton. ’You mean,’ I said sharply, ’you’re not going to Earth?’

’Don’t be silly.’ His tone was irritable. He sank into a chair. ’Damn you, Delton, you’ve been a bad influence on me. Your crass assumption that I’m lost if I deviate in the slightest degree from my purpose actually had me leaning over backward, suppressing all my normal impulses, my natural curiosity, even my mental approach to the subject. That’s over with. There’s only one way to deal with their type of person.’

I offered him a cigarette. ’What are you going to do?"

’I’d like to borrow that invisibility suit you mentioned.’

I brought the two suits out without a word, and offered him the larger: ’We’re much of a height,’ I said, ’but you swell out more around the shoulders and chest. I’ve always used the big one when I’m carrying equipment.’

I saw his gaze on me oddly, as I pulled the second suit over my clothes. ’Where do you think you’re going?’ he said coolly.

’You’re heading for Apartments three hundred to three-oh-eight, aren’t you?’

"That’s right but – ’

’I feel sort of responsible for you,’ I said. ’I’m not going to let that girl be stuck in her job, or be forced to marry some tenth-rater because you get killed at the last minute."

Rand grinned boyishly. ’You sort of like her looks, eh?

OK, you can come along.’

Just before he put on his headpiece, I brought out the glasses. I said: ’We might as well be able to see each other.’

For the first time, then, since we had met, I saw Jim Rand change colour. He stood for a moment as if paralysed; and then his hand reached gently forth and took the glasses. He stood there with them in his fingers, staring as at a priceless gem.

’Man!’ he whispered finally, ’man, where did you get these? I’ve been trying for fifteen years to get hold of a pair.’

‘There was a shipment,’ I said, ’of five dozen to the patrol police on Chaikop. Four dozen and twelve thousand stellors arrived. I figured they were worth a thousand apiece.’

’I’ll give you,’ Rand said tensely, ’ten million stellors for this pair.’

I could not for the life of me suppress a burst of laughter. He scowled at me, snapped finally:

’All right, all right, I can see you won’t sell. And besides you’re right. What the devil does a family man want with them on Earth anyway!’ He broke off. ’How well can you see with them?’

’Pretty good. Help me switch on the lights. That’ll give you a better idea."

It’s really startling how little is known about invisibility suits. They were invented around 2180, and were almost immediately put under government control.

Almost immediately. It was soon evident that someone else was manufacturing them secretly, and selling them at enormous prices. The traffic was eventually suppressed on all the major planets, but it followed the ever receding starry frontiers, its sale finally limited by a single fact:

Only one man in a hundred thousand was willing to pay the half-million stellors asked for an illegal suit.

The cost of manufacture, I have been told, is three hundred stellors.

Try and suppress that kind of profit. Fifty years have shown that it can’t be done.

The strangest thing about the suits is that they work best in bright sunlight. Come twilight, or even a dark cloud, and the wearer takes on a shadowy appearance. In half darkness, a suit is practically worthless.

When the power is switched off, an invisibility suit looks like a certain type of overalls extensively used for rough work. It takes a very keen eye to detect the countless little dark points of – not cloth – that make up the entire surface.

Each one of these points is a tiny cell which, when activated, begins to absorb light. The moment this occurs. the cell goes wild. The more light turned on it, the wilder it becomes. The limiting factor is the amount of light that is available.

That was why I had the lights switched on in my apartment, so that Jim Rand could look at me under conditions where, without the glasses, I would have been completely invisible to him.

It was day-bright in the big hallway, too. These enormous ships always try to give the impression of sunniness even in deepest space. It’s supposed to be good psychology. No one with an invisibility suit could ask for a better light.

As I closed the door of my suite, I could see Rand just ahead of me, a shimmering shape. His suit glittered as he walked, and took on strange, shining light-forms. It blazed with shifting points of colour, like ten thousand diamonds coruscating under a brilliant sun.

It was the sleeping hour; and the long corridors were empty. Once, a ship-officer passed us, but both Rand and I were accustomed to the curious sensation of watching a man walk by with unseeing eyes.

We reached Apartment 300. I used my key of ten million locks – and we were in. All the lights were on inside, and a man lay on the living-room floor, very still. It was one of the men who had been watching Rand in the ship’s lounge. Not the leader, Tansey.

Automatically, Rand floated off like a god of light into the bedroom. I headed for the bathroom, then the spaceroom. When I came back, Rand was kneeling beside the man.

’Been dead,’ he whispered to me, ’about an hour.’

He began to go through the fellow’s pockets, pulling out papers. That was where I stepped forward, and put a restraining hand on his wrist.

’Rand,’ I whispered, ’do you realize what you’re doing?’

’Eh?’ He looked up at me. His face showed as a blurred pool of light, but even in spite of that I could see the surprise in it. ’What the devil do you mean?’

’Don’t look any further,’ I said. ’Don’t try to find out any more.’

His low laughter mocked me. ’Man, are you harping on that again? For all I know, in a minute I’ll find out from these papers what this is about.’

’But don’t you see,’ I said earnestly. ’Don’t you see – it doesn’t matter what it is. It’s simply another big Ridge deal; it can’t be more than that. You know that. There have been thousands like it; there’ll be millions more.

’It may be a new city; it may be mining, or any one of a dozen other things. It doesn’t matter!.

’Here’s your test. You can’t leave half your soul on the Ridge and take half with you. For you, it’s all or nothing. I know your type. You’ll always be coming back, ruining your life and hers.

’But if you can stop yourself now, this minute, this second and go out of here, and dismiss the whole affair from your mind – ‘

He had been listening like a man spellbound. Now, he cut me off brutally:

’Are you crazy? Why, I’ll lie awake nights from sheer curiosity if I don’t find out what this is, now that I’ve been dragged into it.’

His voice took on an arrogant note: ’And suppose I do get off at Zand tomorrow, and stay for a few weeks. Am I a slave to the idea of retirement? It was never my intention to be anything but free to act as I pleased. I – ’

’Ssshh!’ I said. ’Here comes somebody.’

Rand stood up in a leisurely fashion, the true sign of the experienced invisible man. No quick movements! Soundless action. We stepped back from the body as near the door as possible.

It was in such moments that the glasses were priceless. Ordinarily, in a crisis, two invisible men working together are a grave danger to each other’s movements.

The door opened, and four men came in, the last of them being Tansey. He had a white bandage on his nose.

’Price was a damned fool,’ he said coldly. ’He should have known better than to try to murder a fellow like that. Just because we received the eldogram from Grenville telling us that he’d never sent that other message, he –’

Another man cut him off: "The important thing is to slip him into this invisibility suit and dump him through the refuse lock.’

They trooped out into the empty corridors, carrying their invisible burden.

When they had gone, Rand said slowly, grimly: ’So Grenville’s in on this – ’

I stood at the great entrance lock, watching the ship cranes load Rand’s baggage on to the surface craft that had soared up from Zand II.

The planet rolled below, a misty ball of vaguely seen continents and seas, a young, green, gorgeous world.

Rand came over and shook my hand, a big man with a strong, fine face. I couldn’t help noticing the way his hair was greying at the temples.

’I’ve eldogrammed Gady,’ he said, ’that I’ll be there in two or three weeks.’

He saw the look on my face, and laughed. ’You must admit,’ he said, ’that the opportunity is one that I can’t afford to miss.’

’Don’t kid me,’ I said, ’you don’t even know what it’s all about.’

’I will,’ he said, smiling. ’I will.’

I knew that.

His last words to me were: "Thanks for the loan of the suit and glasses. That cuts you in for twenty-five per cent of anything I make.’

I said: ’I’ll see that my agents contact you.’

I watched his big form move off through the lock. Steel doors clanged between us.

As soon as the ship started to move, I went to the purser’s office. He looked surprised.

’Why, Mr Delton,’ he said, ’I thought you were leaving us at Zand.’

’I changed my mind,’ I said. ’Book me through to Earth, will you?’

That was three years ago.

My wife is looking over my shoulders as I write this. ’You can at least,’ she says, ’explain.’

‘It’s really very simple. When I saw Rand come aboard, I eldogrammed my agent on Zand II. He sent a message to Tansey, purporting to come from Grenville, describing Rand, and stating that the man of that description was Artur Blord, who, the eldogram said, must be prevented from landing.

Rand reacted the way I expected. The only thing was, when I saw the girl, I changed my mind. I had my agent wire Tansey that a mistake had been made and that Rand was – Rand.

Tansey grew suspicious, and wired Grenville, who disclaimed all knowledge of the previous eldograms. At this point Price came to my suite to kill me. I used the large invisibility suit to cart his body to Apartment 300; and it was still lying there when Rand and I entered.

The reason I interfered in the first place with Rand’s purpose of retiring was because I wanted to use him to force my interest into the tremendous uranium find that had been made on Zand. I’ve found that I become bored with the actual details of organizing a great mining development, and I do it only when I can’t find a man to whom such details are life’s blood. A man who will moreover let me buy in in some fashion.

Naturally, I used my knowledge of the psychology of spacemen. It’s clear to me now that, once those kinds of forces are set in motion, they can’t be stopped.

I looked up at my wife. ’Well, Gady,’ I said, ’will that do?’

’Except that like a good sport, Mr Rand sold us the house.’

Gady insisted on calling our first-born by my full name: Artur Christopher Blord Delton.

You see, Rand convinced me. A man has to retire some time.